4 takeaways from the UK financial crisis

4 takeaways from the UK financial crisis

December 13, 2022 | By Dean Sevin Yeltekin

What happened.

Newly minted Prime Minister Liz Truss arrived in Downing Street in early September 2022. Less than a month into her tenure, her government announced an economic stimulus program that included £45 billion in tax cuts and zero spending reductions. In a period of high inflation, many economists would have recommended the opposite approach.

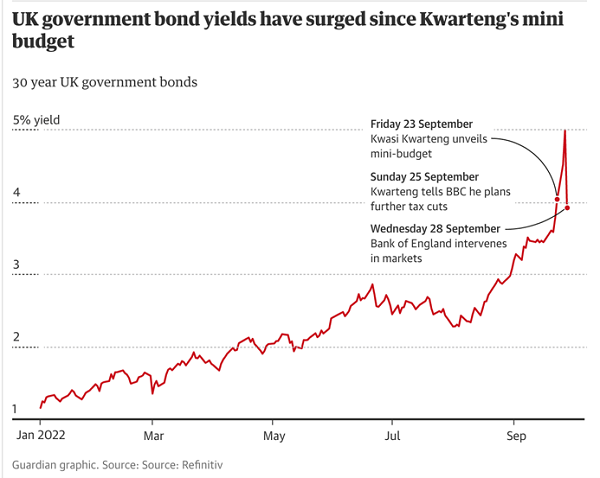

After the announcement, the British pound fell to a record low against the U.S. dollar after it had already been sliding downward all year. At the same time, yields on UK government debts rose from 3.495% to 4.504%. This jump fueled a fire that was already beginning to burn hotter. This year alone, yields on 10-year government bonds have risen 325%, making it more expensive for the UK government to borrow in order to finance its policy commitments.

Meanwhile, the Bank of England had been preparing to begin selling its bond holdings and raising interest rates in an effort to clamp down on inflation. But five days after the Truss government’s announcement, it reversed course and announced it would seek to stabilize UK markets by buying £65 billion in long-term government bonds over a two-week period.

In a public statement, the Bank of England explained its actions: “Were dysfunction in this market to continue or worsen, there would be a material risk to UK financial stability. This would lead to an unwarranted tightening of financing conditions and a reduction of the flow of credit to the real economy.”

If the Bank had not stepped in, the rationale went, the bond market would continue to tumble, threatening the solvency of the UK’s biggest pension funds and insurance companies. With the savings of workers and retirees at risk, it was time to act.

After the Bank of England’s intervention, the pound rebounded slightly and bond yields began to fall again. The Truss government, however, did not rebound. After only six weeks as prime minister, Liz Truss resigned her post.

Key takeaways.

These events may have taken place an ocean away, but they touch on key questions about the role of central banks and elected officials in managing the economy well—questions that hit remarkably close to home.

Upon reflecting on the recent crisis in UK markets, I’d like to propose four takeaways from the situation:

1) When the fiscal and the monetary policies work against each other, breakdown can ensue.

Tension will inevitably arise between central banks like the Bank of England and the Federal Reserve, which are currently raising interest rates to fight inflation, and elected leaders who find that these policies make it harder for them to borrow and spend.

While these two central banks are technically independent, they are acutely aware they are running on a parallel track. In the UK, the once-parallel tracks began racing in opposite directions—with Bank of England employing a contractionary monetary policy to control inflation, while the government announced large tax cuts without a coherent funding scheme. When this happens, disaster can be imminent. It is uncommon to see a large risk premium on UK government debt. Its credibility as a safe asset, built over hundreds of years of fiscal management, was about to be undone significantly with one bad policy move. This is cause for caution for future British and US governments.

2) It’s hard to rebound from a crisis of credibility.

In a 1980 speech to the Conservative Party Conference, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher delivered one of her most famous lines: “You turn if you want to, the lady is not for turning.”

When a central bank or government delivers one message in public—and then turns—they risk plunging themselves into a crisis of credibility. The rapid downfall of the Truss government demonstrated the worst-case scenario for a government that tries to pursue a plan and rapidly walk it back, but the Bank of England has also raised questions of credibility. At a certain point, when will people stop believing public statements? Will they believe the Bank when it announces a plan to raise interest rates by X percent in a given time frame? While the Bank emerged from the crisis far more unscathed than the Truss government, both sides should be wary of further damaging their own public credibility in the future.

3) Elected officials can put central banks in a no-win position.

The Bank of England’s Financial Policy committee has a mandate to ensure the stability of the financial system. Under this mandate, it could justify its bond purchases. But thanks to the actions of the Truss government, it felt compelled to make decisions that attracted criticism from multiple angles.

On one hand, as my colleague Narayana Kocherlakota argued in a recent piece in The Washington Post, the Bank of England’s actions can be viewed as exceeding its authority by undermining the decisions of a democratically elected government. On the other hand, these actions can be construed as a “moral hazard,” shielding governments from absorbing the consequences of risky actions. In this case, the Truss government fell anyway, but there are other plausible scenarios in which it could have survived. Both arguments criticize the Bank of England for stepping in, but the Bank of England clearly believed that not stepping in would defy its own mandate. It’s hard to overstate how tricky these types of situations are for central banks to navigate.

4) This could happen here.

It’s not outlandish to replace the Bank of England with the Fed and the Truss government with Congress in this scenario. If a future Congress enacted a budget with deep tax cuts and no spending reduction, fueling inflation and destabilizing our markets, it could end up in a similar game of chicken with the Fed.

Liz Truss may have resigned—and U.S. politicians will move in and out of office—but the tension between fighting inflation and keeping financial markets stable will remain firmly in place for the foreseeable future. When a government and central bank are aligned on how to resolve this tension, it becomes significantly less risky for financial markets. When they clash, they risk making a bad situation worse.

The Fed is already walking a tightrope, and elected officials can either work to stabilize that rope or make it even more precarious. While the U.S. and UK economies are not identical, clearly, the Bank of England bailout should feel familiar—not because it has happened here, but because it could.

Sevin Yeltekin is the Dean of Simon Business School.

Follow the Dean’s Corner blog for more expert commentary on timely topics in business, economics, policy, and management education. To view other blogs in this series, visit the Dean's Corner Main Page.