Inflation, energy prices, and the Fed

Inflation, energy prices, and the Fed

March 30, 2021 | By Dean Sevin Yeltekin

Note: This article mentions the economic impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. By concentrating on energy prices and inflation, the intention is not to minimize the human suffering caused by the invasion. The humanitarian crisis in Ukraine is far greater and more important than the economic impact.

In the opening days of 2022, inflation was continuing its startling upward climb and supply chains were still untangling themselves amid the disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic. No one wanted to contemplate any other crisis that would worsen the economic state of affairs.

Then, on February 24, Russia invaded Ukraine, precipitating an energy crisis that has fueled the flames of inflation. A month later, the Federal Reserve bounded into action and raised the federal funds rate, hoping to clamp down on inflation without throwing the economy into a tailspin.

As I write, the war in Ukraine rages on, the Fed has embarked on a delicate balancing act, and gas prices are through the roof. There is no better time to ask tough questions about how we got here and where we are headed.

Why hasn’t inflation eased up by now?

As I covered in a previous blog post about U.S. inflation, the steady rise of inflation has taken U.S. policymakers, businesses, and consumers by surprise.

Here are some sobering statistics: According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, overall inflation increased 7.9% between February 2021 and February 2022. The annual inflation rate for February is the highest since January of 1982. For four straight months, inflation has hit new 40-year highs. Gasoline, shelter, and food were the largest contributors to the seasonally adjusted all-items increase.

At the beginning of the year, economists were predicting that inflation would level off as COVID-19 cases declined and supply chains began to right themselves. At the Federal Reserve Board’s June 2021 meeting, Chairman Jerome Powell echoed this view, pointing to a similarly lethal cocktail of spiking demand and supply shortages after World War II.

In his March 21 address at the 38th Annual Economic Policy Conference National Association for Business Economics, Powell doubled down on his previous comments, saying that “forecasters widely underestimated the severity and persistence of supply-side frictions, which, when combined with strong demand, especially for durable goods, produced surprisingly high inflation.” He also pointed to the common theory, now debunked, that COVID-19 cases would rapidly diminish or disappear altogether with the advent of the vaccine.

While Chairman Powell’s explanation is certainly plausible, only time can prove him right. What is certain, though, is that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has made inflation significantly worse.

How has the Russian-Ukrainian crisis fueled inflation?

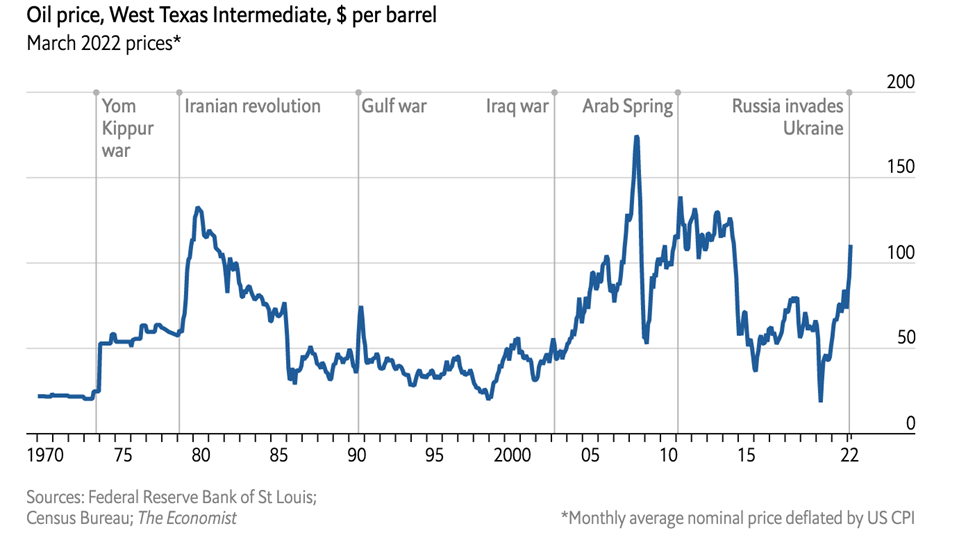

Global oil prices were on the rise before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, as the demand for gasoline dramatically outstripped production following pandemic lockdowns.

The political fallout of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has widened that gap. In early March, President Biden signed an executive order to ban the import of Russian oil, natural gas, and coal to the U.S. in an effort to starve the Kremlin of the resources it needs to fund its attack on Ukraine.

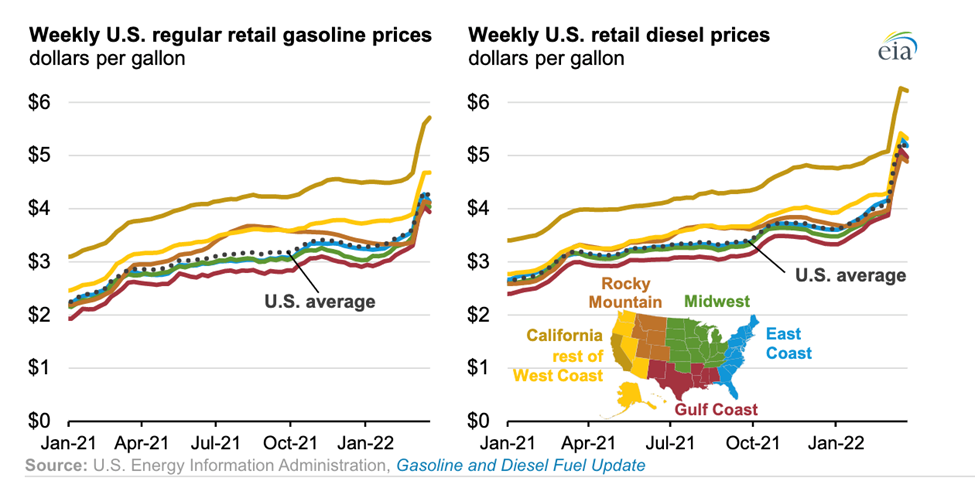

Inevitably, the move resulted in economic pain. In 2021, the U.S. imported nearly 700,000 barrels per day of crude oil and refined petroleum products. At 3% of total U.S. foreign imports of oil and 1% of U.S. supply overall, this shortfall was enough to boost the U.S. national gas price average to $4.24/gallon on March 21.

The impact on U.S. inflation is clear: The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported a 6.6% in the gasoline index in February, which accounted for nearly a third of the all items monthly increase.

How should we expect sanctions to impact energy prices going forward?

In a recent lecture entitled “Sanctions, Energy Prices, & the Global Economy,” economist James Hamilton compares this energy shock to similar events in 1974 and 1979:

Amid inevitable comparisons to the 1970s, Hamilton argues that the U.S. is significantly better positioned to weather oil price shocks than it was 50 years ago. While he doesn’t negate the impact on inflation, he points to the fact that the U.S. is now the world’s largest producer of oil, and its economy is less oil intensive than it once as.

While the U.S. economy might be better-situated than it was in the 1970s, it would be a mistake to minimize the impact of pump prices that are 38% higher than a year ago, particularly for Americans living paycheck to paycheck or businesses heavily reliant on energy, like those in the manufacturing, construction, and shipping industries.

Are there any good alternatives to sanctions on Russian oil?

Unfortunately, alternatives to sanctions are few and far between. Harvard economist Ricardo Haussman has suggested imposing sanctions in the form of a tax so that the country or countries imposing the tax can benefit from additional revenue. The question of who bears the burden of that tax—either the demander (the West) or Russia (supplier)— would depend on the demand elasticity. In this case, demand is more elastic than supply, so a tax would hurt Russia more than the West, unless Russia was able to make up for it by selling to China.

I don’t expect this idea to gain much traction as sanctions are underway. The Biden administration is currently focusing more on softening the shock of higher energy prices. Recently, the U.S. joined 30 other countries in releasing 60 million barrels of oil from strategic petroleum reserves (30 million barrels from the U.S.).

To further cushion the blow of high gas prices, some economists have suggested price caps or direct lump-sum subsidies to consumers. Unfortunately, any measure that could increase current demand, even inadvertently, would only benefit the supplier—in this case, Russia.

What is the Fed’s plan to reduce inflation?

At the time of the June 2021 meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), the Survey of Professional Forecasters was nearly unanimous in predicting that 2021 inflation would be below 4 percent. Obviously, that prediction was completely off base.

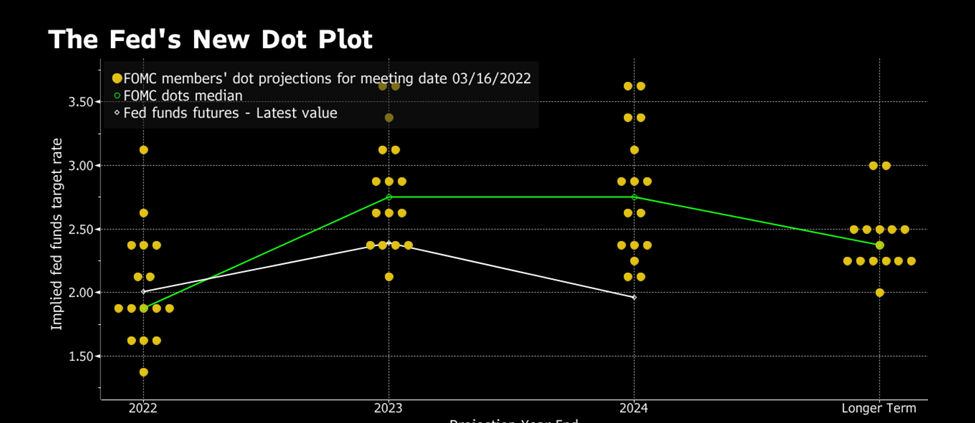

In mid-March, the Federal Reserve voted 8-1 to lift the federal funds rate to a target range of 0.25% to 0.5%, the first increase since 2018. It anticipates six rate increases in 2022 and another two in 2023. In the Fed’s latest Dot Plot, which includes opinions (dots) from each Fed bank president, the median projection is for the benchmark rate to land at 1.9% by the end of 2022 and rise to approximately 2.8% in 2023.

Along with many onlookers, I would have predicted a smaller number of rate increases. Rising inflation clearly called for immediate, robust action, but this more aggressive path came as a bit of a surprise to many.

Source: Bloomberg.com

Can we expect a soft landing for the economy?

Chairman Powell stated publicly that these hikes will help bring inflation down to 2% over the next three years. The trick is bringing down inflation without throwing the economy into a recession. In FOMC projections, the economy achieves a soft landing, with inflation on the decline and unemployment holding steady.

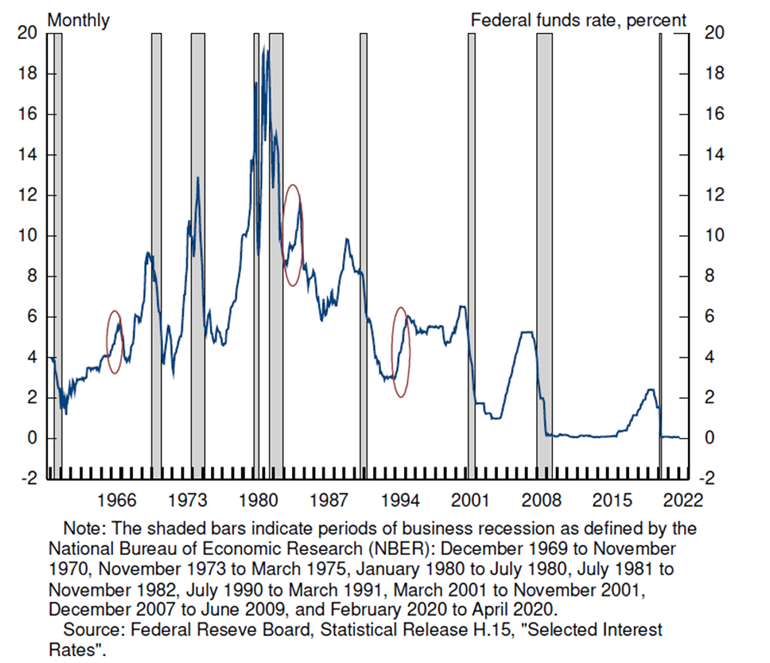

There have been some instances of soft—or soft-ish—landings after the Fed raised the federal funds rate significantly in response to rising inflation. In 1965, 1984, 1994, the Fed pulled off its balancing act without causing a recession.

Will the Fed strike the right balance? I’m cautiously optimistic, but it’s difficult to overstate the complexity of preventing an economic downturn in the context of rising inflation, geopolitical conflict, and a global pandemic. As a nation, we have confronted economic challenges before and come out on the other side, but we have never before confronted this precise combination of factors. These next few months will be pivotal. At Simon Business School, we will continue to analyze and untangle the economic questions that matter most as events play out.

Sevin Yeltekin

Dean, Simon Business School

Follow the Dean’s Corner blog for more expert commentary on timely topics in business, economics, policy, and management education. To view other blogs in this series, visit the Dean's Corner Main Page.