Making sense of U.S. national debt: Part 1

Making sense of U.S. national debt: Part 1

November 17, 2021 | By Dean Sevin Yeltekin

These days, the topic of the national debt seems to surface in nearly every political battle fought on Capitol Hill.

While Congress passed a $1 trillion infrastructure bill with bipartisan support this month, the Biden administration’s sweeping social spending bill is still in limbo while congressional Democrats wrangle over the price tag. In the background, the national debt stands at $28 trillion, and it’s anticipated to reach $89 trillion by 2029 at its current trajectory. The numbers are clear—you can even watch them increase in real-time at www.usdebtclock.org if you’re so inclined—but it’s difficult to cut through the heat of political rhetoric to understand their significance.

I recently asked Dr. Kenneth Judd, a Stanford economist who also happens to be my former Ph.D. advisor, to bring some clarity to the conversation.

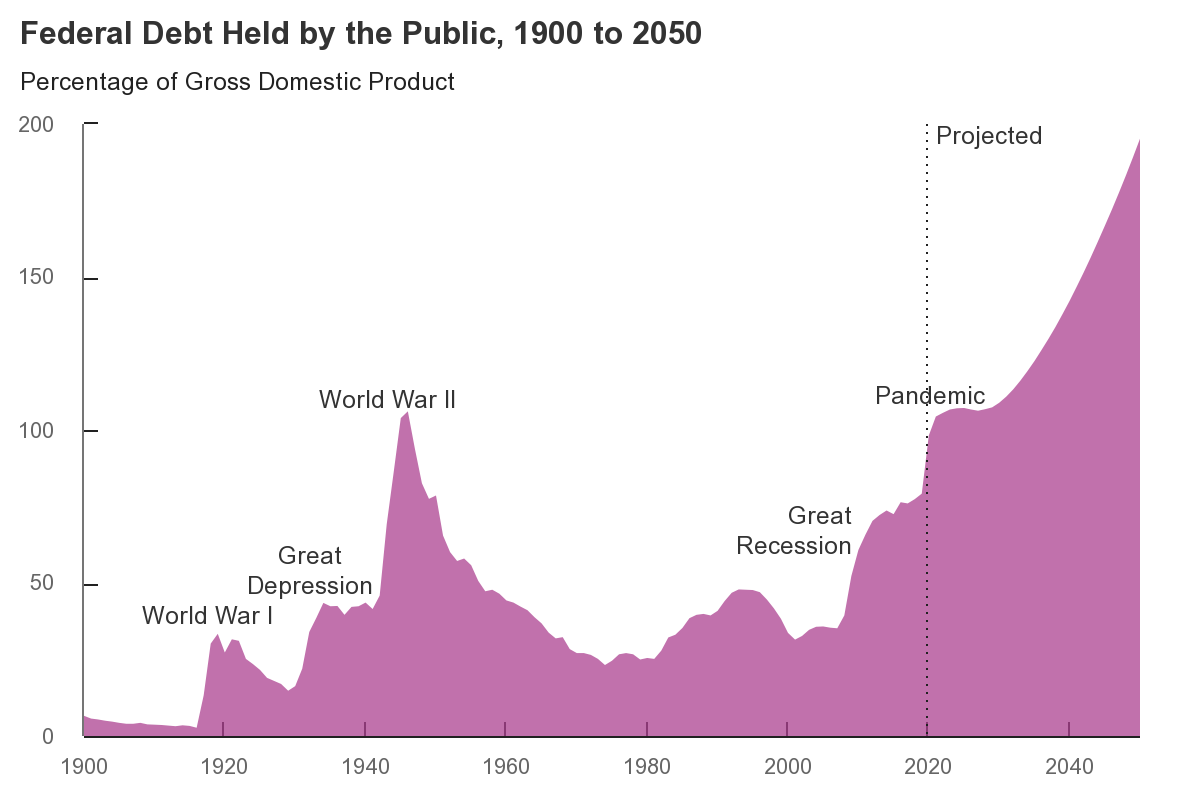

Dean Sevin Yeltekin: The current debt-to-GDP ratio is about 1.25, breaking a record set during World War II. Can you put that into historical context for us?

Dr. Kenneth Judd: The debt-to-GDP ratio was 1.25 back in September 1945, but that didn’t worry anyone at all. In fact, the U.S. was in the early phases of planning for a November 1945 invasion of Kyushu, to be followed by a March 1946 invasion of Honshu and Tokyo. The government was willing to push the debt-to-GDP ratio to close to 2, but the war ended earlier than expected. Postwar inflation reduced the national debt by 25%, which was not surprising given the end of wartime price controls.

Source: Congressional Budget Office

Dean Yeltekin: When you look back over the past 50 years, what were some of the factors that drove significant increases and decreases in the debt?

Dr. Judd: In the 1970s, inflation took a big bite out of the market value of the debt. Then it started to grow with Reagan’s tax cuts and defense spending increases in the 1980s. But Clinton raised taxes somewhat and oversaw a period of economic expansion without major increases in spending, causing the debt-to-GDP ratio to fall in the late 1990s. Then we had the Bush administration with its 2001 tax cuts, two major wars, and expansion of Medicare, as well as the financial crisis of 2008, all of which contributed to an explosion in debt. Debt continued to rise under Obama, first due to the Great Recession and a small stimulus package, and then Obamacare. The rise in debt slowed in Obama’s second term, but the Trump era brought tax cuts and the COVID-19 recession and spending packages.

The key fact is that this debt explosion was mostly self-inflicted due to the mix of tax cuts and spending increases, the failure of financial regulation, and the mismanagement of two wars. No one can dispute the need for action after 9/11, but the U.S. focused on Iraq, the unnecessary war, before it had finished the job in Afghanistan, allowing both to drag on far too long.

Dean Yeltekin: How concerned should we be about the trajectory of the debt?

Dr. Judd: I’m not all that worried about the current debt-to-GDP ratio. Ultimately, this number doesn’t reflect the true burden of debt on an economy. The right way to look at it is to consider the flow of payments to finance the debt relative to the flow of GDP. That is still a low number. With proper management and sensible tax reform, we should be able to deal with our debt. Of course, it’s much easier said than done. We’re finding expensive ways to keep Americans alive longer and longer. Medicare spending is going to explode. That’s what worries me most.

Dean Yeltekin: Why aren’t markets responding to the rising debt?

Dr. Judd: Markets aren’t responding because they’re completely confident in the credibility of U.S. debt. Countries like Japan, with an aging population, and China, with a declining labor force, are still willing to lend at very low interest rates. The world loves our paper as long as we make it safe for them.

Dean Yeltekin: Do you view the ongoing political battles over the debt ceiling as a threat to this sense of safety?

Historically, the debt ceiling was just an opportunity for the party out of power to complain about the party in power. There was never any serious talk about letting the debt ceiling be a binding constraint. Only in the Obama years did the GOP use this issue in a serious way, and we’re seeing the same thing during the Biden administration. I’m hoping that when push comes to shove, the party out of power backs off in these situations. Defaulting on our debt would be a complete disaster. The Constitution requires us to honor our debts. Cash transfers, like Social Security checks, would be the obvious way to quickly respond to hitting the debt ceiling, and the scenarios get worse from there. We must maintain the reputation of U.S. government debt as a safe investment.

Dean Yeltekin: What are some of the policy changes that will improve the debt outlook?

Dr. Judd: From a strategic perspective, the Federal Reserve is missing an opportunity. The U.S. Treasury issues long-term debt, but the Fed buys it and finances its purchases with short-run borrowing. Right now, the U.S. is choosing to finance deficit spending at short-term interest rates instead of locking in low rates over the long-term. It should take advantage of the historically low long-term interest rates.

Second, we have to talk about sensible tax reform. Some of the elements of Biden’s “Build Back Better” plan, like the proposed “surtax” on Americans with an adjusted gross income of $10 million and above, are things the ultra-rich can easily avoid. They just move income over time or through other channels to avoid the surtax. Instead, I’m in favor of some variant of the Hall-Rabushka flat tax proposed by my colleagues at the Hoover Institution.

We also have to consider a greater investment in human capital through tax deductions. Incentives matter. If you look across the country, the states with the highest itemization rates are also home to the greatest concentrations of world-class institutions of education. The cap placed on the state and local tax (SALT) deduction by the 2017 Trump tax reforms is an impediment to human capital formation, because it reduces the incentives for voters and legislatures to invest in education and workforce development.

Dean Yeltekin: How will the increasing pressure to tackle climate change impact debt levels?

Dr. Judd: The U.S. must lead on climate change, or nothing will happen. By implementing a sizable carbon tax, the federal government will be able to generate significant revenue while providing incentives to invest in developing alternatives to fossil fuels. A carbon tax would also allow us to impose tariffs on imports from countries that fail to tax carbon, pushing them to implement carbon emission policies as well. This will help deal with the debt as well as push the world in a climate-friendly direction.

Dean Yeltekin: Any parting thoughts?

Dr. Judd: I sympathize with some of the more negative outlooks on the national debt, but the good news is that future projections can change quickly. Don’t forget that only 20 years ago, we were actually looking at a budget surplus and a shrinking debt and worrying about what the Fed would do if there were no Treasury bonds to buy. Things changed for the worse, but they can change again for the better.

Sevin Yeltekin

Dean, Simon Business School

Kenneth Judd is an economist who works on tax policy and the application of modern computational methods and tools. He currently serves as the Paul H. Bauer Senior Fellow at Stanford University's Hoover Institution.

Follow the Dean’s Corner blog for more expert commentary on timely topics in business, economics, policy, and management education. To view other blogs in this series, visit the Dean's Corner Main Page.