Smarter health insurance plan design

Smarter health insurance plan design

November 8, 2023 | By Elena Prager

As a nation, we spend 18% of GDP on health care. A rapidly growing segment of that total health care spending comes directly from patients’ pockets. Between 2016 and 2021, out-of-pocket health spending ballooned by about 65%, from $300B a year to just under $500B a year. Below, I explore why out-of-pocket spending is favored by employers and health insurers and how we can better use those dollars.

The high share of dollars in our economy spent on health care—far higher than in any other high-income country—motivates insurers and employers to look for ways to use those dollars more efficiently. Insurance plan design has two levers for promoting efficient spending. The first lever is constraints and incentives applied to health care providers, such as requiring physicians to obtain prior authorization before treating patients with certain expensive treatments. The second lever is constraints and incentives for the patients themselves, in the form of cost-sharing. Cost-sharing is the umbrella term that describes insured patients spending money to access health care through co-pays, coinsurance, and deductibles.

This blog post investigates whether and how we can improve our collective return on investment by improving the design of cost-sharing in health insurance. I draw on over a decade of cutting-edge research and recent experiments, including my own research. The result is seven research-driven insights about health insurance design:

1) Certain patient cost-sharing is useful.

There is good reason to require patients to pay something for some of the care they receive. With a thoughtful cost-sharing design, it’s possible to reduce or maintain total health care spending and provide better value for dollars spent.

Consider a simplified but illustrative example: A patient who is enrolled in a self-insured employer’s health plan needs a routine colonoscopy. She has two hospitals nearby; the slightly farther one has a substantially lower price. If she drives 10 minutes to get her colonoscopy at the nearest hospital, the total cost to her and the employer will be $2,300. If she drives an extra five minutes to the next-nearest hospital, the cost will be just $900. Without any cost-sharing, the patient has no reason to go to the farther hospital, so she’ll get her colonoscopy at the $2,300 hospital. With modest cost-sharing for the more expensive hospital, there is a good chance she will go to the less expensive hospital. That decision saves the insured employee pool $1,400. The employer can put that savings toward more generous premium subsidies for employees, or more generous coverage for other types of health care.

2) Certain cost-sharing is harmful or useless.

While some cost-sharing can be useful in getting patients to shop around, more is not always better. Health insurance is intended to insulate people from crippling medical expenditures, and too much patient cost-sharing can undermine that goal. Nearly one in five Americans carry outstanding medical debt (with an average debt of $2,400), and nearly one in ten Americans report either delaying or forgoing medical care because of cost.

But even patient cost-sharing that falls short of being burdensome is not necessarily beneficial. Some cost-sharing merely shifts spending onto individual patients and their families rather than spreading it out among patients in a larger pool. This kind of risk-shifting might be defensible if it helped reduce total spending, like we saw in the colonoscopy example, but it often doesn’t. The problem with many cost-sharing designs is that they simultaneously fail to move total spending and expose patients to greater risk, so patients experience little benefit.

3) An ideal cost-sharing design would achieve two goals that are in direct opposition to each other.

An optimal design would simultaneously achieve two goals:

- Reduce overall spending by shifting patients toward lower-priced treatments or providers. The spending reduction could be used to finance cheaper premiums or more generous coverage of other health care.

- Protect patients from financial risk by minimizing cost-sharing amounts and differences across options.

Unfortunately, these two goals are incompatible. It’s unrealistic to make all health care options free to patients and at the same time expect to nudge patients toward more cost-effective options.

We have to settle for the best achievable alternative instead of the theoretical ideal. That means we accept some financial risk to patients, but only if we get something valuable in exchange for that risk. In other words, we should only use cost-sharing designs that are effective at reducing overall health care spending.

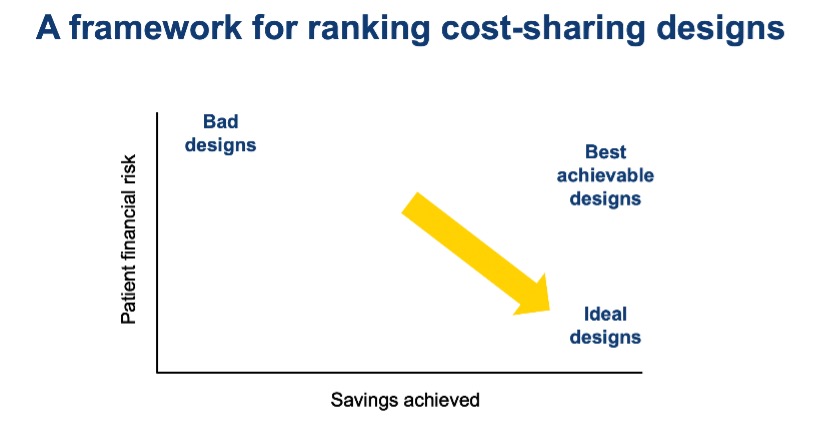

The framework below (see Figure 1) is useful for visualizing how ideal, achievable, and bad designs fit together. The horizontal axis represents the cost burden on a health system, while the vertical axis represents the degree to which a design exposes patients to financial risk. The ideal design saves the health system money while limiting patient exposure to financial risk, so it is located in the bottom right corner of the chart.

Given the impossibility of achieving an ideal design, we should look toward an achievable design in the top right corner of the chart. An achievable design exposes patients to risk while also saving the system money that can be diverted to other helpful uses.

We should avoid the top left corner of the chart, where patients are exposed to a high level of risk but no savings are achieved. Designs in this top left corner are just plain bad.

Figure 1

4) Reference pricing and tiered networks are best at reducing overall health care spending.

Here is a list of cost-sharing designs, some more common than others:

High deductibles: the patient pays first $X of health costs incurred each year

Coinsurance: the patient pays X% of price of each service

Reference pricing: the patient pays every additional dollar above $X for a service

Tiered network copays: the patient pays a pre-determined $ amount for each provider

Rigorous research has demonstrated that the last two cost-sharing designs, tiered networks and reference pricing, are most effective at nudging patients toward efficient use of health care dollars.

A tiered network begins with a health insurer negotiating prices with providers in the market. As a simplified example, take a small market with four hospitals and suppose the insurer has negotiated prices for inpatient care of $11,000, $14,000, $15,000, and $17,000 with the four hospitals, respectively. The next thing the insurer will do is organize the hospitals into “tiers.” The lowest-priced hospitals will go in Tier 1, the middle-priced hospital in Tier 2, and the highest-priced hospital in Tier 3. Patients will pay $250 out-of-pocket if they get inpatient hospital care at a Tier 1 hospital, regardless of what that care is, but they will pay $500 if they get inpatient care in Tier 2 and $750 in Tier 3. This design is intended to nudge patients toward Tier 1 hospitals, which saves the whole system more money than the patient pays out of pocket.

Both tiered networks and reference pricing designs make shopping for health care comparable to shopping in a grocery store. In both designs, patients can easily see the price of every product before they have received care. Moreover, that price doesn’t change after the fact if it turns out the patient has complications that require additional care, or needs a slightly different treatment than initially planned. With coinsurance or deductibles, unexpected changes to the scope of care will also change the out-of-pocket payment, making prices unpredictable and rendering price-shopping functionally impossible.

5) High-deductible health plans, coinsurance cost-sharing, and complex price transparency are inferior options.

High-deductible health plans, coinsurance, and price transparency tools are far more common than tiered systems and reference pricing. Unfortunately, these designs fail to reduce health care spending by getting patients to price-shop, but nevertheless expose patients to considerable financial risk. Recent evidence shows that they do not help patients choose lower-priced providers. All they do is deter patients from seeking health care, including care that medical professionals agree is high-value and cost-effective, like regular vaccination.

6) Simplicity beats sophistication.

The best achievable designs are simple and user-friendly, with pricing that is predictable and comprehensible. Some economists argue against designs like tiered networks, arguing that patients should pay different out-of-pocket prices within a tier if providers in that tier have different overall prices. They might advocate for more sophisticated out-of-pocket prices that fully reflect all the variation in total pricing. The problem with this logic is that patients are not robots with infinite information processing capacity. They are usually stressed, sick, and pressed for time when making health care decisions. We should design for real humans in real-world situations, not for experts who spent years studying the health care system and have infinite time to consider their options.

7) It’s time to transition away from cost-sharing designs that fail to reduce total spending.

High deductibles remain one of the most common cost-sharing designs. From 2006 to 2016, their market share among patients insured through an employer plan grew from 5% to 30%. High-deductible health plans have an even larger market share on the Obamacare exchanges.

The accumulated body of evidence tells us which kinds of cost-sharing reduce total spending and which ones do nothing but burden patients. It is time to transition away from the ones that fail to reduce spending. Armed with the evidence, insurers can start making these changes themselves.

Employers that have the scale to be active procurers of health insurance can also demand simpler designs from their insurers. Many small employers don’t have the expertise or bandwidth to advocate for better insurance designs. But large employers employ roughly 65% of American workers, a large enough share to move the market.

Researchers and economists need to do better, too. Early economic models hold that deductibles are the optimal class of cost-sharing designs. But these outdated models only work when we assume away the many complexities of real patients, such as the fact that the right treatment isn’t always known in advance. In a real-life setting, we now know that simple, comprehensible cost-sharing designs do best.

Elena Prager is an assistant professor of economics and management at Simon Business School.

Follow the Dean’s Corner blog for more expert commentary on timely topics in business, economics, policy, and management education. To view other blogs in this series, visit the Dean's Corner Main Page.