Villains or victims?: What to make of U.S.-listed Chinese companies

Villains or victims?: What to make of U.S.-listed Chinese companies

March 2, 2022 | By Joanna Wu

In December 2021, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) finalized rules that would allow it to delist foreign companies whose auditors fail to cooperate with U.S. regulators. The move came as no surprise to anyone who has observed the heightened tensions between Washington and Beijing when it comes to U.S.-listed Chinese companies. Below, I discuss some of the myths and facts surrounding these companies.

Why should U.S. investors care about this issue?

Investing in U.S.-listed Chinese companies is perhaps the most convenient way for U.S. investors to gain exposure to China’s vast and fast-growing economy. The significance of Chinese companies to the U.S. capital market should not be understated. Let’s put it in perspective with some numbers.

• Alibaba’s 2014 debut on the New York Stock Exchange raised $22 billion, making it the largest IPO (Initial Public Offering) in U.S. stock market history.

• Despite recent U.S.-China tensions, 30 Chinese companies made initial public offerings in the U.S. in 2020, accounting for 15% of all IPOs in the U.S. and 59% of all cross-border IPOs.

• As of May 2021, there were 248 Chinese companies listed on major U.S. stock exchanges with a combined market capitalization of $2.1 trillion.

Are U.S.-listed Chinese companies legitimate investments?

Suspicions of financial fraud have dogged many U.S.-listed Chinese companies. Skeptics of their stocks point to the spectacular collapse of Luckin Coffee, the Chinese equivalent of Starbucks. In May 2020, shares in Luckin Coffee plummeted 80% following a whistleblower report alleging that the firm had overstated its revenues in a massive fraud that began prior to its U.S. IPO in the previous year. Some may also recall the Chinese reverse merger (CRM) wave a decade ago. CRMs accounted for roughly one-quarter of all reverse mergers and about 85% of all foreign reverse mergers in the U.S. in the 2010s. The SEC subsequently delisted many of the CRMs for having committed financial fraud.

In a reverse merger transaction, a private firm acquires a publicly traded firm (a so-called “shell”) and gains control of the public company. This provides the private firm with a backdoor channel to go public without an IPO, which eliminates the need for an underwriter, IPO prospectus, or SEC registration statement and allows it to avoid scrutiny by the investment and regulatory community. It was, and perhaps still is, a commonly held belief that low-quality Chinese firms took advantage of the opacity associated with reverse mergers to gain access to the U.S. capital market and defraud U.S. investors. But anecdotal evidence and popular beliefs aside, what do the data say about the quality of CRMs? When looking at the CRMs during the peak years of the 2010s, around 17% eventually faced fraud allegations (reflected in SEC enforcement actions, class action lawsuits, or media reports), in contrast to around 7% of non-China reverse mergers. Of course, it goes without saying that fraud allegations are not equivalent to proof of guilt and that the frequency of fraud allegations reflects both the likelihood of fraud commission and the level of public and private scrutiny. But other metrics, like the frequency of accounting restatements, also suggest lower reporting quality of CRMs. At the same time, the stock return performance of CRMs as a group, including those accused of committing fraud, is no worse. In fact, they’re somewhat better than their matched non-China reverse merger firms. The overall conclusion is that despite their lower reporting quality, CRMs are still a class of legitimate investments for U.S. investors.

Why do Chinese companies come to the U.S. market to raise capital?

To understand the strengths and weakness of the U.S.-listed Chinese stocks, it’s helpful to understand why Chinese companies seek a U.S. stock market listing in the first place. Currently, China has the second-largest stock market in the world, after the U.S. But a peculiar feature of China’s stock market is that only profitable firms are qualified for listing. Take Amazon, for example. It would not have qualified for an IPO in China as a startup because it made losses for almost a decade after its IPO in 1997. As a result, some promising high-growth Chinese firms seek overseas listings, especially in the U.S., because they are ineligible to list at home. The U.S. is home to the world’s largest and most liquid stock market. Listing in the U.S. also “bonds” a foreign company to America’s stringent litigation and regulatory environments, sending a favorable signal to investors about a company’s quality. This is part of the reason why some of the highly innovative Chinese businesses, such as Alibaba, have chosen to come to the U.S.

In the crosshairs of both sides.

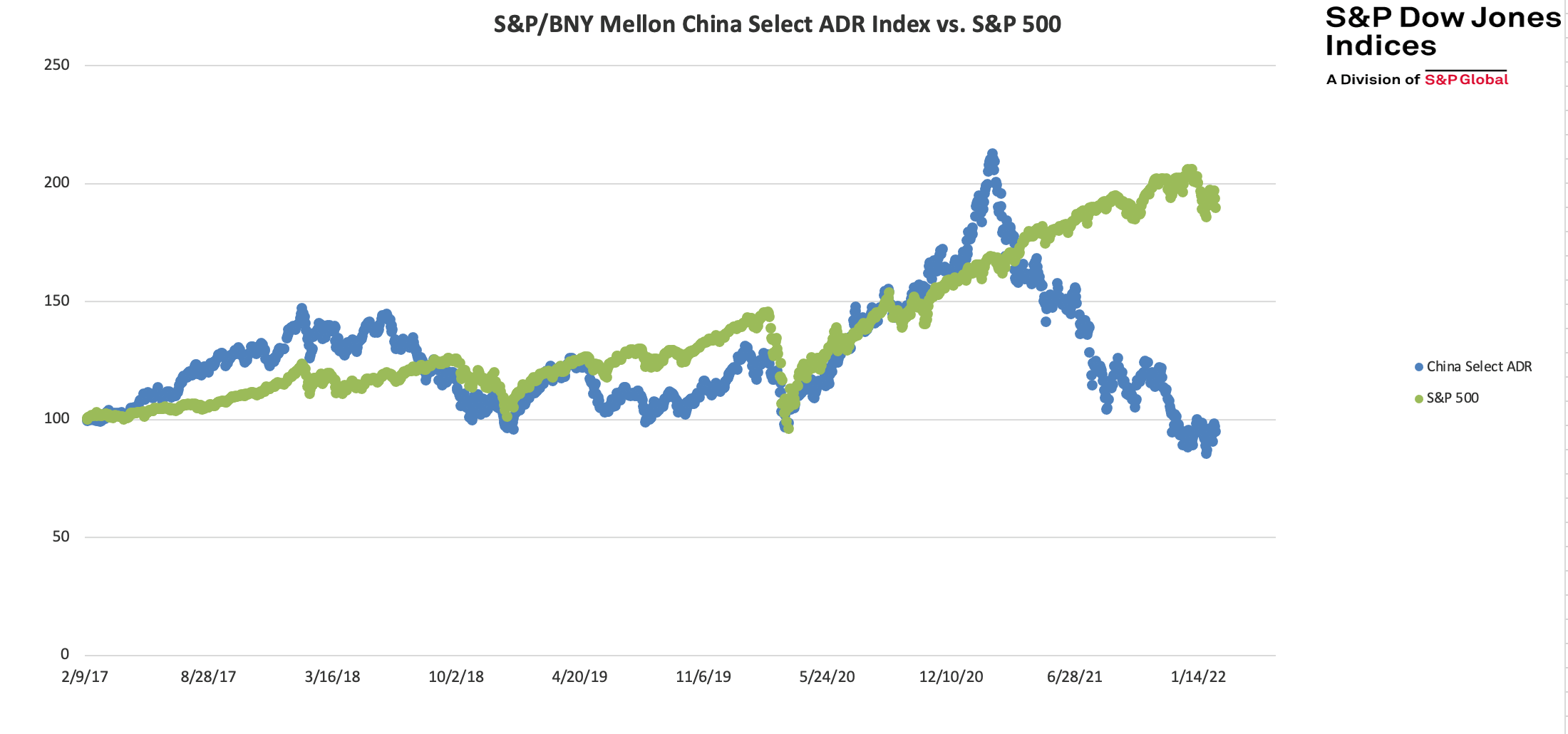

Souring U.S.-China relations have caught U.S.-listed Chinese firms in the middle. Their stock performance has certainly taken a beating as of late (see chart below).

There are a few major flashpoints and sources of uncertainty.

One of these is the longstanding dispute between the U.S. and China regarding the U.S. Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB)’s ability to inspect audit work conducted on operations within mainland China. China has refused to give access to the PCAOB, citing sovereignty concerns. However, failing to provide access could result in the U.S. listed-Chinese firms being delisted en masse in a couple of years. The two sides appear to be on a collision course here.

At the same time, the Chinese government has also come down hard on U.S.-listed Chinese companies recently. These include the last-minute cancellation in 2020 by Chinese regulators of Ant Group (an affiliate of Alibaba Group)’s Hong Kong IPO, Chinese regulatory sanctions imposed on Didi Global within a week of its New York IPO in 2021 for cybersecurity reasons, and the recent crackdown in 2021 by the Chinese government on the private tutoring sector. The implications of the crackdown are broader than the education sector itself because of a ban on the sector’s use of the Variable-Interest-Entity (VIE) corporate structure. The VIE structure, through contractual arrangements, allows foreign investors to obtain the economic benefits of the underlying business (i.e., the VIE) without direct ownership control and has been used to circumvent Chinese government restrictions on foreign ownership in certain industries (e.g., high tech). The VIE arrangement does not give foreign investors direct equity ownership in the underlying businesses located in mainland China, which would have run afoul of Chinese regulations, but it also potentially offers less protection for the rights and claims of foreign investors.

Many overseas-listed Chinese companies, such as Alibaba Group, use the VIE corporate structure. It’s important to note that the broad legitimacy of this structure hinges on the future regulatory position of the Chinese government. The following is the related risk warning in Alibaba’s most recent annual filing with the SEC:

“If the PRC government deems that the contractual arrangements in relation to our variable interest entities do not comply with PRC regulations on foreign investment, or if these regulations or the interpretation of existing regulations changes in the future, we could be subject to penalties, or be forced to relinquish our interests in those operations, which would materially and adversely affect our business, financial results, trading prices of our ADSs, Shares and/or other securities…”

The bottom line.

On one hand, there are risks associated with information opacity, weak investor protections, and high political uncertainty. And it goes without saying that large-scale delisting of these stocks, either imposed by the U.S. government or prompted by the Chinese side, will limit the set of investment opportunities available to U.S. investors. On the other hand, China’s rapid economic growth also promises great rewards. As with any investment, buying stock in U.S.-listed Chinese companies involves tradeoffs—and any wise investor should be well-informed before making the leap.

Many of the statistics cited in this blog are presented in a survey paper written by Professor Wu with Professor Clive Lennox of the University of Southern California. For further details and citations to the relevant studies, click here.

Joanna Wu is the Susanna and Evans Y. Lam Professor of Business Administration at Simon Business School.

Follow the Dean’s Corner blog for more expert commentary on timely topics in business, economics, policy, and management education.